The Capitalist Production of Consciousness

Table of Contents

Assessment: Progress & Consciousness

1. Troubles of Progress

2. The Law of Human Progress

3. The Capitalist Production of Consciousness

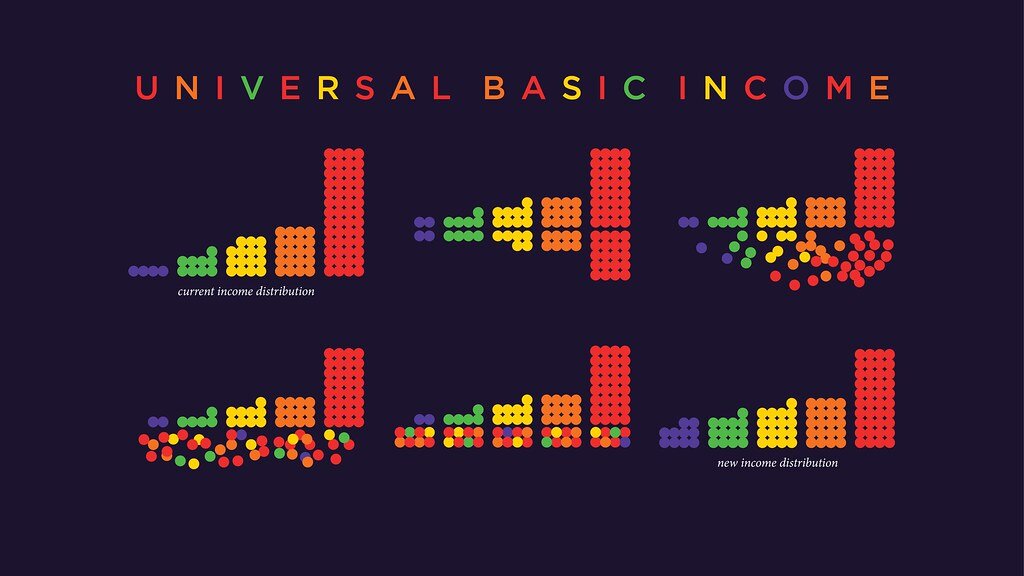

A Response: Universal Basic Income

1. Universal Basic Income

2. Critiquing UBI

3. Next Steps: A Modernized NIT

Beyond: Post-capitalism & the Economic Problem

1. Beyond UBI

2. Conclusions: New Trips, New Problems

...

WE cannot much longer ignore the discomforting truth that the economies we’ve inherited from the twentieth century are poorly designed for the production of human beings. As digital technologies weave economic logic deeper into the temporal fabric of everyday life, we’re debasing economic society’s most complex, valuable, and neglected production: human consciousness.

The psychedelic community uses the term set and setting to describe how the kind of trip one has after ingesting a shriveled mushroom, or a tab of acid, deeply depends on the social, mental, and environmental conditions present throughout.

But what we experience as “ordinary consciousness” is itself a psychedelic state: the mind manifested in tune with its set and setting. Society functions as the set and setting for the everyday trip of ordinary consciousness.

As economic development interlaces all aspects of society with economic incentives, ordinary consciousness is molded by economic forces. Left undisturbed, the invisible hands of capital will set the trajectory for human development, adjusting the production of human beings in the interests of capital.

Redesigning the economy to elevate that trajectory requires comprehensive reform, but we can begin with a universal basic income (UBI). By decommodifying a basis of time for all, UBI changes the logic of everyday life. Altering the imperatives governing this most elemental level of society - the everyday - produces effects that ripple throughout. As new ways of living are made viable for all, exploratory behaviors yield new developmental possibilities that arise from within the shell of the old.

II. Contemplative Economics

I made this connection between economics and consciousness during my 11th month in Asia. I was sitting on the floor of a dusty bookshop in Northern India, rolling my gaze across the tilted book spines. It turns out, after spirituality and meditation books, the most popular subject left behind by decades of angsty travelers was economics. Strange, I thought.

This was a connection I sought while studying economics and philosophy in college. It felt intuitive, but the bridge between economics and subjectivity was a dead end in my department (indeed, it remains a dead end in most mainstream economic discourse).

And so it wasn't until after graduating, when I set aside the idea of an economics that concerns itself with human consciousness, that I began discovering the broader inquiry of heterodox economics and critical theory. Asia's used bookstores supplied me with the broader education school hadn't.

Nearly 100 years ago, German Marxists of The Frankfurt School harped on this link between economic conditions and the production of consciousness. Capitalism, they argue, produces an individual’s subjective experience just as it does a Ford automobile. But this line of criticism largely died with them. At precisely the moment in history when digital technology began globalizing capitalist cultural conditions, the countervailing schools of criticism tapered off.

I didn't find God or enlightenment out there. But I did discover a direct theoretical grammar, a way of looking at the unnecessary human suffering caused by the under-scrutinized relationship between economics and consciousness.

This grammar was lost not only to economists, but contemplatives too. Economists are trained to stay in their lane, avoiding any evaluative, normative judgments of values and preferences. Economists do not concern themselves with the kinds of humans economic systems produce.

But contemplatives, too, neglect how the socioeconomic structure of society is dominating the conditions of conscious experience. India was full of meditation retreats populated by white westerners, but few discussed how to democratize the economic privileges that made their meditation trips possible. Few asked whether we might structure society in such a way that we don’t require retreats from it in order to probe life’s deeper questions.

In the 60’s, psychedelic psychologist Timothy Leary coined the motto: Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out. But too often, dropping out was misunderstood as exiting from society, whether for an ashram in India, or a commune on your father’s golf course. As technology globalizes capitalist cultural conditions, the capacity to ‘drop out’ is an illusion of privilege. For most, society is not an optional game, but a mandatory set and setting for their ordinary consciousness.

As philosopher Zachary Stein puts it: “Our entire lives are shaped by the ways we interface with the wage labor system—we are only as free as the ways available to us to make money."

The Frankfurt School detested the kind of consciousness capitalist environments produce, but hardly suggested remedial action beyond condemning capitalism and making vague gestures towards emancipatory art and mass revolution. But you cannot critique a new world into being. You must design for it.

I’ll explore universal basic income (UBI) as one possible intervention in the hyper-capitalist distortion of human development. By securing decommodified time for all in the form of universal, unconditional income, UBI enables behaviors, relations, and projects - ways of living - that transcend the logic of capital.

III. Hyper-Capitalism and Human Development

Hyper-capitalism is a term economist Thomas Piketty uses to describe the confluence of neoliberal capitalism and the digital revolution. Neoliberalism refers to the variety of capitalism that arose in the 1970’s. It emphasizes deregulation and privatization, discourages all taxes (especially on capital), and promotes free-market individualism over state-mediated collectivism. Combined with the globalizing force of the digital revolution, neoliberalism evolved into hyper-capitalism:

Hyper-capitalism combines existing tendencies towards the commodification of physical space with new digital and algorithmic capacities that convert attention into capital, incentivizing the total commodification of time.

The totalizing commodification of both space and time drives hyper-capitalism’s monopolization over the production of consciousness. The set and setting of everyday life is increasingly imbued with commodity logic. The emergent consciousness cannot help but follow suit.

On the physical plane, hyper-capitalist expansion is remaking our public spaces into advertising zones and business plazas. Cities are designed by the profit motive. But “the question of what kinds of cities we want,” economic geographer David Harvey writes, “cannot be divorced from the question of what kind of people we want to be, what kinds of social relations we seek, what relations to nature we cherish, what style of daily life we desire”. As adaptive creatures, the logic embedded in our physical environments plays a causal role in the humans we become.

While the commodification of space is at least visible to us, the commodification of time occurs out of sight. Hyper-capitalism commodifies time either by freeing up surplus time through productive innovations and feeding that surplus back into the production process, or by pushing deeper into previously un-commodified areas of life.

What the culture industry began by reducing leisure time to commodified passivity was picked up by machine learning algorithms. Attention is now converted into capital by capturing behavioral data to improve the algorithms. All time is now ripe for commodification; uncaptured time is unrealized value.

Commodifying time reduces optionality, constraining the potential behaviors we pursue within it. The logic of capital accumulation becomes the arbiter of viable behavior inside commodified time.

Expanding across and commodifying both frontiers - space and time - hyper-capitalism conditions our behaviors, ideas, and ways of relating with each other. It conditions the very kinds of humans we’re becoming.

While hyper-capitalism is an unparalleled system for accumulating capital, it’s a dubious guide for human development. The past 50 years of capital-led development created an adaptive cycle that reproduces and entrenches commodity logic in the evolutionary process.

This logic favors standardization over diversity, undermining the social complexity that drives robust evolution. Commodity logic cannot recognize human interiority as a value in itself; only as a factor of production. Unseen and undervalued, mental health languishes. If the trajectory of social development over the past 50 years constitutes ‘progress’, the process has derailed.

At the same time, a global society participating in a shared division of labor and connected by digital information flows makes possible cooperative leaps of progress unlike history has ever seen. To be sure, hyper-capitalist afflictions are balanced by a staggering list of advances. Medicines, mortality and literacy rates, hygiene, and innovative technologies. But the good can no longer justify the bad. The balance is broken.

We must revisit what progress means, and how it proceeds. To do so, I’ll draw from Henry George’s law of human progress, Karl Widerquist’s work on the physical basis for voluntary trade, and the post-capitalist visions of Martin Hägglund and Thomas Piketty.

UBI can play a vital role in this process. By decommodifying a basic level of time for everyone, it makes behaviors beyond commodity logic viable. These new diversities of behavior could introduce new directions for human development by enabling exploratory behaviors from the bottom up, rather than imposing ways of living from the top down.

UBI is not a panacea, but perhaps what George calls a “true reform”: one that makes all other reforms easier. This is nowhere more clear than its role in addressing what I call the paradox of markets. By decommodifying our foundation of basic needs, UBI shores up the basis of voluntary exchange that activates socially desirable markets.

But I’m not here to evangelize for UBI. We’ll complement positive appraisals with a sobering account of its criticisms. We’ll ask whether UBI is a capitulation, rather than alternative, to neoliberalism. We’ll consider human nature, and whether securing decommodified time for all might simply lead to widespread idleness. And since UBI is a tax-funded program, we’ll ask whether UBI is an unjustified transfer of income from those who earn it to others who simply receive ‘something for nothing’.

Of course, there are more straightforward reasons why UBI is becoming a policy of vigorous debate. But here, my focus is on the farther reaches of UBI: how, by decommodifying time, it alters the production of consciousness and the direction of human development.

My aim is twofold: first, analyze how hyper-capitalism produces consciousness, and why the present mode of production is problematic. Then, explore how UBI decommodifies time, opening up new forms of participation and possibilities that transform the system from within.

The Troubles of Progress

“…the social difficulties existing wherever a certain stage of progress has been reached, do not arise from local circumstances, but are, in some way or another, engendered by progress itself.”

~ Henry George

AT the frontiers of progress, we find the jarring juxtaposition of society at its best and worst simultaneously. Henry George, the most celebrated political economist of the late 19th century, noted how the worms that rot the core of civilizations tend to emerge internally, from the process of progress itself. The progress of past civilizations, he notes, has always given rise to the means of their own downfall.

It’s not yet an indictment to say that capitalism produces consciousness. All socioeconomic environments create conditions for particular modes of subjectivity to evolve. Economies play a natural role in shaping the environments for human development.

But the corrosive properties of our development were amplified by the coalescence of neoliberalism and the digital revolution. Digital technologies sharpened the existing logic of neoliberalism, where capital accumulation is the sole proxy for social development.

These two forces spiraled together, creating history’s first true world-system. A world-system is a single set and setting stretched across the globe. A homogenous, standardized evolutionary environment. It maintains coherence across vast geographical spaces through a shared division of labor with global markets for its goods and services. Instantaneous global information and capital flows circulate like blood coursing through the world-system’s internet-connected veins.

Zachary Stein writes that there has been, at least since the 1970’s, “a truly planetary culture. Or better: a global ideology broadcast from a polycentric capitalist world-system touching every corner of the Earth.”

The digitization of capitalist cultural conditions goes beyond globalizing the existing set and setting. It’s transforming the internal structures, the mediums that connect us to the logic of capital. Markets and economic institutions are no longer confined to atoms, but exist as diffused, digitized bits. As we’ll explore, digital technologies dematerialized economic institutions. Factories and assembly lines defined the capitalist environments of 1945 - 1971. The internet deterritorialized these modes of production, as media theorist Jonathan Beller notes:

“Cinema brings the industrial revolution to the eye…and engages spectators in increasingly dematerialized processes of social production...mass media, taken as a whole, is the deterritorialized factory, in which spectators do the work of making themselves over in order to meet the libidinal, political, temporal, corporeal, and, of course, ideological protocols of an ever intensifying capitalism...The media, as a deterritorialized factory, has become a worksite for global production.”

But the metaphor doesn’t go quite far enough. If the industrial revolution was brought to the eyes, hyper-capitalism extends through them, into the brain. Digital technologies drive the conflation of capital growth with social development deeper into the human being.

It’s in this new neuronal space of dematerialized social production that we begin to see the consequences of human development subordinated to capital. As the dematerialized logic of capital streams into our brains - those windows into the soul that are now always plugged into screens designed to mine the capital of attention - these influences pervade and remake the neuronal space itself.

According to philosopher Byung-Chul Han, 21st century humans suffer from a new signature affliction unique to hyper-capitalism’s immaterial modes of production: neurological illness. The digitally amplified logic of capital remakes neurons into factors of production. Immaterial exploitation under hyper-capitalism does not incite revolution, so much as depression, anxiety, and burnout:

“Every age has its signature afflictions...From a pathological standpoint, the incipient twenty-first century is determined neither by bacteria nor by viruses, but by neurons. Neurological illnesses such as depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), borderline personality disorder (BPD), and burnout syndrome mark the landscape of pathology at the beginning of the twenty-first century. They are not infections, but infarctions; they do not follow from the negativity of what is immunologically foreign, but from an excess of positivity.”

Note the distinction: these pathologies aren’t foreign, from outside the system. They arise from within the system itself, as the “excess of positivity”. The process of turning humans into products of hyper-capitalism generates externalities that manifest as neurological illnesses. Here we witness George’s theory in action. Our progress is giving rise to the means of neurological, civilizational decay.

Hyper-capitalism mass-produces, at a global scale, these means of decay. Fashioned by this process, we reproduce the systems that make us. We propagate the means of our pathologization. We’re creating, and spreading, the worms that will rot the core.

But as the psychedelic lens suggests, by redesigning our environments, we can redesign ourselves. By redesigning our environments, we can nudge the trajectory of social evolution. Henry George provides a framework to understand where our systems of progress went wrong, and how we might redesign them for the better. He calls this framework the law of human progress.

The Law of Human Progress

“The tower leans from its foundations, and every new story but hastens the final catastrophe.”

~ Henry George

IN Henry George’s Progress and Poverty, he derives the law of human progress: “the law under which civilization advances.” For George, healthy progress depends upon two conditions: association, and equality.

Association refers to the size of the network of humans peacefully cooperating to do what needs doing. Today, we refer to this network as the division of labor. The larger this network, “the greater the possibilities for improvement.”

This suggests a world-system is not inherently problematic. A world-system with a shared division of labor and cooperative political institutions is a realization of George’s condition of association.

Where progress creates problems - whether that of poverty which troubled George so, or the invasive commodification and global homogenization that we address here - is by failing to adhere to the second condition of progress: equality.

Equality, for George, was indistinguishable from justice, or freedom. Today, his notion of equality more closely resembles what we refer to as equal access. George’s equality is a commitment through which we secure the advances made by each generation as common property for the next. That is to say, progress yields advances that are to be sedimented in an ever-rising ground of common property on which everyone stands. The less of one’s resources they must spend gaining access to the advances already made, the more resources they can devote to exploring further progressive purposes.

Without a commitment to equality, civilization rests upon uneven foundations. The fruits of progress are available only to those lucky enough to be born onto high ground. By treating progress as collectively owned common property, its fruits must be democratized.

“Thus association in equality is the law of progress. Association frees mental power for expenditure in improvement, and equality, or justice, or freedom - for the terms here signify the same thing, the recognition of the moral law - prevents the dissipation of this power in fruitless struggles.”

In George’s time as in ours, we have powerful association with meek equality. We’ve seen tremendous surges in our capital stock and productive capacity. And yet, for a vast portion of the population, wages still tend towards the minimum that affords a bare living. It isn’t that wages don’t allow access to the basic elements of life in the modern world. But for most, affording access to that supposed common property of progress leaves nothing leftover. The inequality does not manifest in access, so much as in time.

The severity of time inequality suggests why an equal decommodification of time for all citizens could be a radically progressive strategy. By treating a basic level of income as the unconditional common property of all citizens, even those lowest on the income distribution can begin to achieve access to what they need without trading all of their time in exchange. People gain optionality in how they spend their time.

Taken to its extreme, this logic culminates in the case made by philosopher Martin Hägglund. He argues - in harmony with Karl Marx - that the surplus time created by capitalist innovation should be treated as common property. Doing so requires collective ownership of the means of production. In the past, labor unions succeeded in capturing a portion of surplus time for workers with the creation of the weekend and 40-hour workweeks. But relying on labor advocacy accepts the inherent conflict between workers’ interests and capitalism’s growth imperative.

For Hägglund, collective ownership of the means of production dissolves the conflict. It leads to collective ownership of the surplus time capitalism generates. In this logic, the ownership of time creates the conditions for freedom and progress: “In short, our freedom requires that we can own the question of what to do with our time. For Marx, political progress is measured by the degree to which it allows for such freedom.”

This is one way to think about progress: the progressive democratization of free time. Not that we all miraculously get more free time, but we gain more agency in deliberating how, and where, the surplus time created by progress is invested. Marx drew a distinction between the realm of necessity and the realm of freedom. In the former, our actions are dictated by pursuing the means for survival. For Marx, freedom implies that necessity does not control our actions. Progress means the democratized transfer of time from the realm of necessity to the realm of freedom.

Applying George’s conditions, free time is not something we purchase on the market. It’s a product of progress that we must collectively own as a sedimented layer of common property beneath our feet. As progress builds, that foundation grows.

By increasingly separating the totalizing logic of capital from how we spend our time, we begin dismantling the mechanism that monopolizes the production of consciousness and co-opts human development. To begin, we can study the interwoven history of capitalism and consciousness. Understanding how they came together better equips us to take them apart.

The Capitalist Production of Consciousness

IN a sense, consciousness has always been a product of economics, at least indirectly. An economy is what emerges from the network of arrangements and technologies a society uses to fulfill its needs, survival predominant among them. Michael Pollan - a writer who studies the interplay of nature and culture - writes in his study of psychedelics: “Most of the time, it is normal waking consciousness that best serves the interests of survival - and is most adaptive.”

What is adaptive for survival within an economy becomes an invisible hand that shapes “normal waking consciousness”. Normal consciousness is a function of what is adaptive for survival, mediated through economic arrangements.

The economic project of arranging ourselves to optimize for survival - what economist John Maynard Keynes calls the economic problem - governs what modes of consciousness are most adaptive for survival within that network of arrangements. The most adaptive modes of consciousness become normalized as the default consciousness within that society.

This is the logic behind calling society a set and setting for the everyday trip of ordinary consciousness. There’s nothing new about it. But while consciousness has always been economized, it has not always been commodified.

I. Edward Bernays

The indirect economization of consciousness occurred as economics created the schedule, possibilities, and prevailing time uses of daily life. By defining existential possibilities, economics indirectly shaped the environments where consciousness develops. The conditions that would lead to the commodification of consciousness bloomed when a direct relationship was established between economic logic and the structure of consciousness. Few did more to create these conditions than Sigmund Freud’s nephew: Edward Bernays.

Like a puppeteer who discovered hidden strings controlling the human mind, Bernays used Freud’s discovery of the unconscious to manipulate conscious behavior. From the 1920’s on, he taught companies how to market and appeal directly to the unconscious, turning consumption into a psychological activity. This created a two-way bridge connecting economic growth with the psychology of citizens.

In his 1928 book, Propaganda, Bernays writes:

“The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country. We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of...we are dominated by the relatively small number of persons [...] who understand the mental processes and social patterns of the masses. It is they who pull the wires that control the public mind, who harness old social forces and contrive new ways to bind and guide the world.”

This was a perversion of psychoanalysis, employing it for profit by capitalizing on repression rather than wrestling shadows to light. Identifying repressions became the stimulus behind consumerist culture.

If hyper-capitalism is the total integration of the logic of capital with the fabric of society, this early bridge made the integration possible. Though the mid-20th century is often hailed as the ‘Golden Age of Capitalism’, market society overwhelmingly dominated and shaped social psychology.

II. Markets and Behavior Regulation

Market societies are complex systems that regulate behavior, often by imperceptible means. It’s no accident that Adam Smith’s famous hand was invisible. Even with no tangible, explicit force that governs how individuals in a market society behave, there are nevertheless regulatory dynamics that align behavior with market structures.

Markets always arise from an edifice of conditions. Those conditions govern the tendencies of behavioral adaptation therein. The mistaken notion of “free” markets merely sublimates the mechanisms of control they claim to transcend.

Some conditions that underlie markets are beyond our control, others are the result of choices we make, or neglect to make. Public and regulatory policies, long derided as intrusions upon free markets, are actually conditions that determine what market dynamics emerge. This frames market design as a project for human development. Designing markets is to design the environments we adapt to.

The system dynamics we’re awash in - homogenized behaviors that erode social complexity, neurological afflictions, and gaping inequalities - are problems of market design, rather than markets themselves.

Like computer programmers, we can go back through the design code to locate the bug. In this case, the market design of neoliberal capitalism traces back, in large part, to Friedrich Hayek. The bug lies in his inadequate understanding of the necessary conditions for meaningful freedoms in a market society.

Hayek was well aware of the intimacy between economics and the structure of our lives, quoting approvingly in his seminal Road to Serfdom from Hilaire Belloc’s history of capitalism: “The control of the production of wealth is the control of human life itself.” Hayek saw markets as technologies to decentralize and democratize the power that previously accumulated in centralized governments.

But Hayek failed to properly account for the invisibility of market dynamics that regulate and control outcomes just the same as government. Without sufficient democratic institutions in place, markets merely took power away from the government and placed it on auction, for the highest concentrations of unregulated capital to claim.

As Martin Hägglund points out, Hayek saw no relevant difference between negative and positive freedoms. For Hayek, “liberty”, or the absence of explicit, tangible coercion was sufficient to constitute meaningful freedom. But this fails to account for all the invisible hands at play in the economy.

The notion of positive freedom suggests that we need more than the absence of explicit oppression. Positive freedom recognizes those meaningful freedoms in a market society that require further conditions and resources to act upon or realize one’s freedoms. A young black woman born in poverty in the South Side of Chicago does not have the same freedoms as a young white male born into a wealthy family in Manhattan. But the relevant unfreedoms are implicit, the result of invisible hands that Hayek’s theory of freedom neglects.

This neglect at the base of Hayek’s political philosophy skews all that was built upon it. Market design informed by his theory, which dominated the landscape from 1971 - 2008, failed to deliver on the promise of democratizing and decentralizing freedoms:

“Hayek cannot see the problem in question, since he reduces freedom to liberty. As long as we are not directly coerced to act in one way rather than another - i.e., as long as we have formal liberty - we are free in the relevant sense for Hayek…As long as we can make a choice without anyone forcing us or telling us what to do, we are free. Such a formal conception of freedom, however, is utterly impoverished…Freedom requires the ability to participate in decisions regarding the form of life we are leading and not just the liberty to make choices.”

Unregulated markets - by means such as the loosening of controls on capital and dismantling the Bretton Woods Agreements in 1971 - were the first condition for the global eruption of hyper-capitalism. The inadequacy of Hayek’s freedom was embedded in the globalized system. With free rein, capital converted the global environment into that which best serves its commodity logic: a system of mass-production. A global market society emerged that was simultaneously everywhere (the same across the globe) and nowhere (invisible).

Mass-producing the conditions for human adaptation runs counter to the logic of evolution. In evolutionary terms, the development of life thrives when the spectrum of mutations are as diverse as possible. More distinct mutations mean more options for advantageous adaptation.

Globalizing economic coherence does move in the direction of George’s first condition of progress: widening our spheres of association. But it falls short of the second, equality, which for George was synonymous with freedom.

This is why we can’t merely reject globalization. Scaling from isolated localities to a global division of labor affords unique opportunities. The relevant questions become how to maintain differentiation across connected adaptive environments? How do we imbue market design with democratic institutions that actually decentralize power? How do we decouple homogenization from globalization?

But before we can answer these questions, we must explore the second condition that enabled the hyper-capitalist world-system: the digital revolution. New forms of digital media would amplify the rapidly expanding logic of capital. It did not only expand outwards, but inwards, colonizing and remaking human perception to the specifications of capital.

III. Dematerialization: Where Have the Factories Gone?

“Technologies such as cinema and television are machines that take the assembly line out of the space of the factory and put it into the home and the theater and the brain itself, mining the body of the productive value of its time, occupying it on location. The cinema as deterritorialized factory, human attention as deterritorialized labor.”

~ Jonathan Beller

The means of production, the infamous French duo Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari write, relocated from buildings to brains. The factors of production evolved from assembly lines to neurons. The digital revolution deterritorialized factories, as if dissolving solid matter into millions of pixels that are streamed, transmitted, injected via new financialized media platforms directly into the mind.

Deleuze and Guattari reference the dominant forms of media in their time - television and cinemas - but all forms of media are communication platforms between cultural logic and individual subjectivity. Media is inherently interactive and educational, in that we learn through participation. As we consume media, media consumes, alters, and reproduces us.

Media theorist Yves Citton names the process by which digital media reconfigures human subjectivity electrification:

“Electrification is in the process of reconfiguring our collective attention, at a global level, according to self-reinforcing dynamics that profoundly restructure the way in which we perceive and evaluate our lived experiences.”

As omnipresent screens electrify attention, their governing logic remakes perception itself. From behind the iPhone, laptop, and television, companies vie for attention – the most prized form of capital. But screens run two ways. From our end, while we occupy every stray moment with aimless scrolling, we are engaged in the kind of repetitive doing that underlies our process of becoming. Electrified desire does the work of coercion, opening time, attention, and psychology to the preferences of capital.

The result is what Jonathan Crary calls a revolution in the means of perception:

“Capitalist modernity has generated a constant re-creation of the conditions of sensory experience, in what could be called a revolutionizing of the means of perception.”

Deterritorialized factories dissolved into thin air, but there they remain, unseen. As neurons become the factors of production, commodity logic pervades the entire substrate of thought. There is no quarantined time. All time is mined as a source of value for the growth of capital. In an environment of perfectly commodified time, what else can we become but instruments of capital? The self, as subjectivity ensconced in monopolized time, becomes commodity. The pure commodification of time is the total commodification of the self.

But we can invert this logic to understand why policies like UBI can intervene in the production process. Decommodifying time opens the self to ways of living beyond commodity logic.

Universal Basic Income

“Capitalism: a system that generates artificial scarcity in order to produce real scarcity...The artificial scarcity - which is fundamentally a scarcity of time - is necessary, as Marcuse says, in order to distract us from the immanent possibility of freedom.”

~ Mark Fisher

IF progress is conceived as growing our collective ownership over free time - time with both the negative freedom from necessity, commodification, and coercion, and the positive freedom to engage with the world and exercise our capacities - we might frame this as pursuing a zone of universal basic decommodification.

Making decommodified time common property means it must be universal, while the realities of our resources, needs, and capacities, dictate that it must remain basic. There are many reasons UBI is swinging back into popular discourse today: some fear robots will automate away the labor we depend upon to earn our livelihoods; as a means to end domestic poverty amidst 21st century plenitude, some prefer universal programs to targeted welfare; others see UBI as a way to decrease the imbalance of power and wealth between labor and capital; and still others believe UBI might herald the dawn of a new society. Here, I’m interested in UBI as a means for achieving this universal basic decommodification of time.

At present, decommodified time is distributed through a cosmic slot machine. Luck and privilege are the main determinants of who receives it. Those who maintain that a strong work ethic is the main driver of success fail to grasp how one’s work ethic is itself the product of a complex and arbitrarily received latticework of luck and privilege.

I’ve spent the past five years studying UBI. I’ve inhabited every position along the spectrum, from starry-eyed supporter enthralled to its promises, to disillusioned skeptic, dismissing UBI as a well-intentioned, though naive lurch for utopia.

Applying these various perspectives to UBI, we’ll explore three positive dimensions: universal basic decommodification, the betterment of well people, and the paradox of markets. And three dimensions of UBI criticism: the capitulation problem, the human nature problem, and the free rider problem. We’ll complement these discussions with a splash of pragmatism (conspicuously absent from most UBI advocacy), grounding them in the realities of how much UBI would cost, and how we might pay for it.

Universal Basic Decommodification

“Economy of time,” Karl Marx writes, “to this all economy ultimately reduces itself.” Even invoking social complexity by a different name, he writes: “…the multiplicity of its [society’s] development, its enjoyment and its activity depends on an economization of time.”

In harmony with Marx, Frankfurt School philosopher Theodor Adorno writes that “free time depends on the totality of social conditions.” There is no separation between how we spend our time and the socioeconomic arrangement of society. Hyper-capitalism is the total economization of time. Appropriating time is the fuel to hyper-capitalism’s monopolization of consciousness.

Without direct intervention, this dynamic is unlikely to relent. The commodification of time is not arbitrary, but the very engine of capitalist growth. "The expanding commodification of natural resources and life-activities is not optional but necessary for capitalism to sustain itself”, Hägglund writes.

Here’s how it works: the profit motive drives innovation that creates technological progress and improves productivity. Increasing productivity decreases the necessary production time for existing goods and services, creating surplus time. But capitalism cannot recognize surplus time as inherently valuable. Value is only measured, only shows up in the calculus of capitalism, once it generates a quantifiable return. So that surplus time is reinvested back into the production process, creating surplus value, or higher profits that show up on the accounting sheets. Capitalism sustains growth through this cyclical generation of surplus value.

By decreasing necessary labor time, more surplus labor time is generated that can be reapplied back into the production process. Surplus labor time reinvested back into production generates surplus value - increasing the labor input to production increases the value created.

Capital depends upon this surplus labor time to feed the recursive cycle of growth. This is one reason why predictions of 15-hour work weeks from luminaries and economists alike, from Bertrand Russell to Keynes, always fall flat. The time made available by new technologies is always reclaimed by the logic of capital. “Capital is interested in the expansion of only one type of unbound time,” writes political economist William James Booth, “namely, surplus labor time. More briefly, we might say that capital frees time in order to appropriate it for itself.”

The existential implications cannot be overstated. Time envelopes us. Time is the matrix of development. How we spend our time, what we do with this moment, and that one, steers the process of our own becoming. Author Jorge Luis Borges takes this a step further, insisting that not only do we become in tune with our time, we are time:

“Time is the substance from which I am made. Time is a river which carries me along, but I am the river; it is a tiger that devours me, but I am the tiger; it is a fire that consumes me, but I am the fire.”

Earlier, we noted how invisible hands align human behavior with market design. Here, as we become time, we take on its qualities. Commodified time makes the self into a commodity because the self is made through time.

Inside such a system, the universal provision of unconditional income functions as a blockade erected against the total commodification of time. Time is indeed money, and money is time. With a UBI, we are given greater capacity to maintain a dimension of our lives beyond the logic of capital. As these dimensions are maintained for everyone, they empower alternative rationalities to gain momentum from the bottom up.

Sociologist Erik Olin Wright adds: “UBI...expands the potential for a long-term erosion of the dominance of capitalism by channeling resources towards noncapitalist forms of economic activity…[it] does so in ways that puts in place a building block of an emancipatory alternative.”

These spaces must be built inside the hyper-capitalist world-system, for there is no longer an outside. This is why, for Marx, shortening the working week was the prerequisite for “the true realm of freedom.” UBI is just a different approach taken to the same cause: decommodifying time by claiming some of the surplus time generated by productivity gains for ourselves, rather than for continued growth.

What UBI achieves, inside the context of the hyper-capitalist world-system, is universal basic decommodification. Each receives a dividend of decommodified time from the collective ownership of social progress.

The Betterment of Well People

As psychedelics finally begin recovering from the 60’s, there is a concerted effort to reintegrate their use via more prudent and culturally accepted channels. Beginning with terminal cancer patients and PTSD victims, psychedelics are being introduced through medical and therapeutic channels that focus on the lowest extremes of the mental health spectrum.

But by focusing on only the tail-end extreme of mental health, we promote adaptation to a norm that elides critical reflection. Focusing on suffering, without a complementary inquiry into what constitutes “health”, merely assimilates those who suffer into an uncritically accepted notion of health. As that old Jiddu Krishnamurti quote goes, “It is no measure of health to be well adjusted to a profoundly sick society.”

This state of affairs conflates mental health with adaptation to society’s norm, which is itself merely the default consciousness that results from its set and setting. There are no assurances that society itself has been designed to promote a healthy form of default consciousness. There is little investigation into whether the default mode is itself healthy.

The psychedelic community is aware, even wary, of this conflation. To point to the broader applicability of psychedelic potential, the community minted the term: the betterment of well people.

When Michael Pollan interviewed Roland Griffiths, head of psychedelic research at Johns Hopkins, Griffiths acknowledged: “Culturally, right now, that’s a dangerous idea to promote [the betterment of well people]...[but] We are all terminal, We’re all dealing with death. This will be far too valuable to limit to sick people.”

Just as psychedelics are too valuable to restrict to sick people, improving our economic conditions is far too potent to restrict to the poor. The middle class that targeted welfare programs strive to assimilate the poor into is itself unwell.

All, whether poor and traumatized or well-off and healthy, are enmeshed within the totalizing logic of capital. Our subject is not confined to the extremes, but prevalent throughout the entire income distribution. When the norm is sick, it’s the entire system that requires change.

There is perhaps no better recent work that demonstrates the illnesses of normalcy, and motivates the economic betterment of well people, than anthropologist David Graeber’s bullshit jobs.

Bullshit Jobs

“There is something terrible, ridiculous, outrageous going on, but it’s not clear whether you are even allowed to acknowledge it and it’s usually even less clear who or what can be blamed.”

~ David Graeber

Graeber’s book Bullshit Jobs is a series of case studies that suggest something is terribly wrong with the normalized, default mode of consciousness society produces. Our focus of reform must extend beyond merely the poor to include the betterment of so called “well people”. Poverty is not the last loose end of capitalist society - the “spiritual violence of modern work” plagues the entire income distribution.

A bullshit job is a form of paid employment so pointless and meaningless to society that even the employee cannot justify its existence. The spiritual violence that results is insidious, because it’s practically invisible.

“Huge swathes of people, in Europe and North America in particular, spend their entire working lives performing tasks they secretly believe do not really need to be performed. The moral and spiritual damage that comes from this situation is profound. It is a scar across our collective soul. Yet virtually no one talks about it.”

Graeber contends that bullshit jobs are not bugs, but features of the variety of capitalism that arose in the 1970’s. When the economy loosened international controls on capital, dismantled pro-labor social policies, began privatizing industries into deregulated markets, and spawned an oversized financial sector, the nature of the system changed. It no longer fit the vision of Adam Smith, Karl Marx, or even Ludwig Von Mises. This was the beginning of what I refer to as the hyper-capitalist world-system, a departure from anything recognizable to the very theorists invoked to justify it.

In Graeber’s analysis, we find the familiar notion that society is an evolutionary environment that guides human development. As we design our economic environments, they, in turn, design us. They constitute a set and setting that gives rise to a default consciousness, a norm which is then assumed to be the standard measure of health. But as Graeber cautions, “there is something very wrong with what we have made ourselves”:

“I would like this book to be an arrow aimed at the heart of civilization. There is something very wrong with what we have made ourselves. We have become a civilization based on work - not even ‘productive work’ but work as an end and meaning in itself. We have come to believe that men and women who do not work harder than they wish at jobs they do not particularly enjoy are bad people unworthy of love, care, or assistance from their communities. It is as if we have collectively acquiesced to our own enslavement...This is a disastrous state of affairs. I wish it to end.”

The trajectory of human development, Graeber agrees, has gone awry. To end this ‘disastrous state of affairs’, in which the hyper-capitalist world-system recreates the entire globe into a set and setting that engenders this form of spiritual violence, Graeber proposes a safe-word theory of social liberation.

The safe-word he has in mind is UBI: “Basic income in this sense would, indeed, give workers the power to say ‘orange’ to their boss.” Equipped with a safe-word that grants people the capacity to opt out of exploitative relations, what would remain is an economy woven of willful participation.

The safe-word theory of social liberation envisions UBI functioning as the safe-word that remakes society upon a basis of voluntary, rather than forced, participation. Bullshit jobs would largely cease to exist (or be forced to offer more attractive compensation), as workers would have substantial bargaining power and little reason to accept such employment.

We can develop this insight further by applying political philosopher Karl Widerquist’s work on the physical basis for voluntary trade. This leads us into what I will call the paradox of markets.

The Paradox of Markets

“There is no reason why in a society which has reached the general level of wealth which ours has…that the security of a minimum income should not be guaranteed to all without endangering general freedom.”

~ F.A. Hayek

Progressive ideologies tend to splinter over the role of markets in society. Some see markets as the problem, defining the progressive project as one of curtailing the extent of markets in society. Others believe redesigned markets, together with more democratic institutions, are the solution. Here, I’ll attempt to synthesize both perspectives by exploring UBI as a design tool that simultaneously curtails the coercive extent of markets, while redesigning their foundations so that markets become more just, efficient, and socially desirable.

I call this the paradox of markets: basic levels of decommodification are the necessary preconditions for markets to function as the mechanisms of free exchange and decentralized complexity that economic theorists have long praised them as. Basic levels of decommodification actually make for better markets. A UBI that decommodifies our basic needs by providing for them unconditionally improves the outcomes in all markets that rest upon this decommodified base.

But what is to be decommodified? What does this mean in practice? For this, we turn to Karl Widerquist, who answers the question by deriving the physical basis of voluntary trade.

The Physical Basis of Voluntary Trade

Market economies are built, justified, and legitimized on what economists call voluntary exchange. Voluntary exchange describes the process of freely and willfully buying and selling goods and services, where each participant is free to accept or refuse the trade. Capitalism, Milton Friedman declares, is ‘the freedom to choose’.

Voluntary exchange, writes Widerquist, is the foundation upon which the house of modern economics stands:

“...when neoclassical economists theorize about the world, they assume voluntary exchange is taking place. Building on this assumption, neoclassical economics goes on to conclude a variety of important results such as that market activity is efficient, that free trade has net positive effects and that markets in which economic agents participate voluntarily make them better off...Although the legitimacy of the market economy is premised on voluntary trade, without a reasonable exit option, the trading system as a whole lacks an acceptable alternative.”

As with any foundation, if voluntary exchange falls, all that’s built upon it follows. Widerquist argues that there exists a physical basis for voluntary trade, without which participants in market economies have no capacity to refuse certain trades. For market exchanges involving life’s essential needs, participants have no exit option, no reasonable alternative. Without access to basic shelter, food, water, and essential goods and services, individuals lack the capacity to refuse certain exploitations and are coerced into trade.

Without options for meeting the physical conditions necessary for truly voluntary exchange outside the scope of markets, there will always exist a dimension of involuntary, coerced exchange. In pre-capitalist societies where private property had not yet claimed all available land, individuals were hypothetically free to cultivate their own land, gather their own resources, and fend for their own survival. But today, all land is privately owned, there are no reasonable alternatives to participating in subsistence markets.

Widerquist concludes that we’re left with two options: the system, as the only realistic option, must unconditionally provide everyone with the physical means required for truly voluntary trade, or we must abandon the appeal to voluntary trade as a justification for the market economy.

Widerquist proposes UBI as the optimal method for providing the physical basis for voluntary trade. By providing a sufficient amount of unconditional income that always allows individuals the realistic option to refuse trade without sacrificing their basic human needs, the pervasiveness of involuntary trade is curtailed. Citizens receive an exit option, the capacity to refuse trades they deem exploitative. Or, in Graeber’s language, a safe-word.

This is the first leg of the paradox of markets: voluntary exchange in a global market society requires the unconditional provision of basic needs.

The Physical Basis for Social Complexity

“The curious task of economics is to demonstrate to men how little they really know about what they imagine they can design.”

~ F.A. Hayek

The lack of meaningful alternatives to market participation at the individual level scales up to system dynamics. Especially if we recall the earlier point, that market societies are complex systems that align individual behavior with market incentives. By providing no choice but participation, no ground to enable experimentation, hyper-capitalism functions as a closed-system with a gravitational pull towards the norm. Its default consciousness sits at the center, and all that circulates in orbit is drawn inward.

Existing within a closed-system that erodes our capacities to explore different ways of living has an ideological effect. Cultural theorist Mark Fisher calls our present closed-system of ideology capitalist realism. The way we organize ourselves is so thoroughly, so singularly consumed by one particular ideology, that we are losing the capacity to imagine alternatives. Our patterns and habits of thought are coming into increasing alignment with the hyper-capitalist commodification of society. We’re losing touch with the ‘outsides’ that place pressure on, or sometimes pierce, a standardized way of thinking.

It’s in this all-consuming sameness of economic ideology that Theodor Adorno concedes to Milton Friedman that capitalism provides the freedom to choose, but subverts the optimism by adding it’s only: “the freedom to choose what is always the same.” The means of control free markets claimed to transcend were merely sublimated into more culturally palatable forms.

Rolling these all into a single point - hyper-capitalism’s tendency to homogenize ways of thinking, Fisher’s capitalist realism, Adorno’s freedom to choose what is always the same - each condemns hyper-capitalism for laboring against, rather than for, the conditions that encourage social complexity.

We can define social complexity as the diversity of possible arrangements and relations in society. For example, a society where everyone lives in monogamous relationships and nuclear families is less socially complex than one where these social arrangements exist alongside polyamorous, communitarian based family structures. The more differentiation among social patterns, the more social complexity.

But hyper-capitalism, a polycentric world system that controls all land and resources under the legal protection of private property, imposes an initial bottleneck on differentiation. As this closed system evolves, an eternal sameness sets upon the world. Frankfurt School philosopher Herbert Marcuse called it “the closing of the universe.” He continues: “By virtue of the way it has organized its technological base, contemporary industrial society...precludes the emergence of an effective opposition against the whole.”

But a UBI that decommodifies our basic needs loosens that bottleneck. It rolls back the eternal sameness. Making the atomic units of market societies - individual market transactions - increasingly voluntary also scales up across the entire economic rationality. As each of these atomic units are afforded the basic needs that make alternatives more realistic, the system floods with increased differentiation from the bottom up.

Differentiation would occur increasingly unbound by the bottleneck of capital accumulation. Social complexity thrives as people’s optionality increases. Affording each individual the means to say “no” raises the optionality threshold of all.

With a realistic exit-option, society then remakes itself as an increasingly voluntarily chosen system. Voluntary participation functions as approval of the system, providing an ongoing democratic election process for the structure of society itself. Those who ‘opt out’ are enabled to construct alternatives that exert healthy pressure from those lost outsides, rather than left stranded without resources.

This is the second leg of the paradox of markets: decommodifying our basic needs creates a foundation that enables precisely the kind of decentralized complexity to emerge that free-market theorists valued.

Since our beginnings, a significant chunk of human time has always been subservient to doing what’s necessary for survival. Societies evolved atop this substratum of necessary activities.

But global society coupled with new technologies and increasing returns to scale offer an unprecedented opportunity. We can complement our expanding spheres of association - George’s first element of progress - with a structural commitment to reducing time inequality. This may allow us, for the first time in history, to design a system that guarantees human needs without exploiting human labor. The market societies that emerge from this substratum would be fundamentally different from those we’ve seen so far.

By designing economic policies with the paradox of markets in mind, we can bolster the foundation of justice and voluntary exchange that theory assumes, while creating better conditions for the kind of complexity to emerge that markets were meant to spur.

Critiquing UBI

THE more radical a proposal, the more scrutiny it should receive. A UBI pegged to the poverty level could occasion the first society built on a foundation of voluntary participation in history. Livelihood has never been provided by a society irrespective of one’s labor inputs. The scrutiny brought to UBI should reflect this scale of magnitude.

Contributing to the scrutiny, I’ll explore three dimensions of UBI critique: the capitalution problem, the human nature problem, and the free rider problem.

The Capitulation Problem

In a brilliant polemic against UBI, sociologist Daniel Zamora lays out the progressive left’s critique: UBI is not an alternative to neoliberalism, but a capitulation to it. Rather than fighting for deeper structural reforms, UBI simply accepts the market’s monopoly over human life.

Recall Hägglund’s critique of capitalism: it must commodify ever more of our lives in order to survive. Its mechanism for doing so is by creating markets where previously there were none, and intensifying the commodification of existing spheres of activity. For Zamora, a UBI simply concedes to this transmutation of all life into the commodity form. He calls UBI a “bioindicator” that indexes neoliberalism’s progress. “In fact”, he writes, “the most viable forms of basic income would universalize precarious labor and extend the sphere of the market - just as the gurus of Silicon Valley hope.”

But as Zamora notes, whether UBI is an alternative or a capitulation depends on the amount of unconditional income it provides and the broader conditions of its implementation. He does not believe that a meaningful UBI is theoretically impossible, but is realistically unaffordable. Surveying a few flimsy funding proposals, he concludes: “an affordable UBI is inadequate, and an adequate UBI is unaffordable.”

The balance between capitulation and alternative boils down to whether UBI can provide at/above the poverty line without defunding all other social programs. Anything below fails to provide the physical basis for voluntary trade, further sedimenting our dependence upon coercive markets.

To assess the critique, let’s introduce the cost of UBI, and how we might pay for it.

The Cost of UBI

UBI has two relevant costs, gross and net. The gross cost reflects the total revenue the government must raise to fund the program. But since funding UBI requires progressive taxation, an upper portion of recipients will wind up paying more in new taxes than they receive from UBI. This creates a canceling out effect, where one receives $12,000 in UBI, but pays $14,000 in higher taxes. The effective cost to them is $2,000, rather than $14,000. The cost of UBI that takes these effects into account is the net cost (For all cost estimations and sources, details may be found in the appendix).

The gross cost of a UBI equal to the poverty level in 2019 ($12,490) for all citizens older than 18 would’ve been roughly $3.2 trillion. Adding a 50% UBI for minors would increase the gross cost to $3.6 trillion.

Moving from gross to net cost is difficult to forecast, as it depends on the specific taxes used to fund it. But to offer a ballpark idea of the disparity between gross and net costs, Widerquist used a series of simplified assumptions to estimate the net cost of a UBI with a $3.42 trillion gross cost: $539 billion, or 15.7% of the gross cost. Other net cost estimates include $900 billion, and $1.69 trillion.

How to Pay for UBI

What would it take to raise $3.6 trillion annually? No single tax is sufficient. UBI is only possible in partnership with broader progressive tax reform. Here, I’ll gather 12 options to raise revenues, including projections that range from the most conservative estimates to the most optimistic for each proposal.

Progressive Marginal Income Tax Rates

Projected annual revenues: $18.9 billion - $70 billion.

Example: Adding an eighth tax bracket for incomes above $10 million taxed at 70% is projected to raise anywhere from $18.9 billion, if no other tax changes are made, up to $70 billion if a broader progressive taxation system is in place.

For a more first-principles approach, readers may consider the idea of a monotonically increasing tax rate that does away with brackets altogether.

Raising Capital Gains taxes

Projected annual revenues: $6 billion - $170 billion.

Examples: Shifting to a carryover tax basis is projected to raise $10.4 billion annually, and taxing capital gains of the top 1% on an accrual basis could yield $170 billion. These projections are for changing methodology, rather than raising rates.

Revenue projections for raising capital gains rates are complex, because outcomes depend on the broader system of taxation. As such, models that predict a $6 billion annual raise in revenue by raising capital gains taxes from 20% to 24.2% are tenuous.

Wealth Tax

Projected annual revenues: $118 billion - $375 billion.

Example: A 2% tax on wealth above $50 million, cranking up to 3% on wealth above $1 billion, is projected to raise $275 billion, annually.

Raising Corporate Taxes

Projected annual revenues: $9.6 billion - $135+ billion

Example: Reforming how the corporate tax is levied often offers more potential revenue than raising the rate. Still, the 2017 tax cuts reduced the corporate rate from 35% to 21%, leading to a $135 billion decline in corporate income tax revenue.

The congressional budget office (CBO) estimated the revenues for a mere 1% increase in the corporate tax rate, finding a $9.6 billion annual increase.

Folding Redundant Welfare Programs

Projected annual revenues: $100 billion - $771 billion.

Example: While total welfare expenditures hover near $771 billion, Wiederspan, Rhodes, & Shaefer (2015) isolate means-tested programs that a UBI or NIT would make redundant, totaling savings of $207 billion.

Land Value Tax

Projected annual revenues: $100 billion - $750 billion.

Example: LVT projections are scant. The most recent academic work we have dates back to 1985. The author estimated that a full LVT could raise 28% of national income, yielding $658 billion in 1981 (28% of national income in 2018 would yield $5.8 trillion).

More recent and sober estimates range from smaller, targeted LVT rates that yield closer to $100 - $200 billion in annual revenue, up to a 5% LVT that raises $750 billion.

Value Added Tax (VAT)

Projected annual revenues: $600 billion - $1.3 trillion.

Examples: CBO estimates for a 5% VAT tax range from $190 billion to $290 billion annually, depending on details. Committees have expanded these findings to estimate that a 10% VAT tax would raise approximately $600 billion per year.

Estimates on broader-base 10% VAT tax expect revenues of $1.3 trillion per year.

National Income Tax

Projected annual revenue: $1.2 trillion.

Example: A national income tax was proposed by Emmanuel Saez & Gabriel Zucman in 2019 as an alternative to the VAT, which economists worry is avoidably regressive. The tax applies to all income - capital and labor - at a single flat rate with no deductions or exemptions. They estimate a 6% national income tax could raise $1.2 trillion annually.

Financial Transaction Tax (FTT)

Projected annual revenues: $60 billion - $75 billion.

Example: A o.34% broad-based FTT could raise a maximum of 0.4% of GDP, or $75 billion.

Greenhouse Gas Emissions Tax / Cap and Trade

Projected annual revenues: $100 billion - $210 billion.

Examples: A tax of $25 per metric ton on most greenhouse gas emissions in the US could raise slightly over $100 billion annually, while a tax of $49 per metric ton of carbon dioxide could raise closer to $210 billion annually.

Reducing Defense Department Budget

Projected annual revenues: $59 billion.

Example: Reducing the defense department’s budget by 10%, phased in over a 10-year period, would save $59 billion annually.

Social Security Reform:

Projected annual revenues: $200 billion - $500 billion.

Examples: By replacing one of every three dollars of social security received with UBI, recipients could increase their overall receipts while saving $324.2 billion.

Alternatively, raising the cap on social security payments up to $250,000 would raise an extra $80 billion, while subjecting earnings greater than $250,000 to a 12.4% payroll tax could raise $122 billion, annually.

Total Range: $2.6 trillion - $5.6 trillion.

I am under no delusions that we could sensibly enact all these reforms and raise $5.6 trillion. These taxes cannot all be implemented at their upper projections, and implementing some would eliminate the possibility of implementing others.

For example, in Gabriel Zucman & Emmanuel Saez’s 2019 book, they propose a tax plan that combines four of the above: a wealth tax, corporate tax, higher marginal income tax rates on both labor and capital, and their proposal for a national income tax (a flat tax with no deductions on all labor and capital income). They project these four taxes would raise $1.8 trillion annually:

Given the spectrum of possibilities, together with a concrete view of how these taxes can come together, hopefully we generate a sense of the possibilities at hand. We can push back on Zamora’s diagnosis. An adequate UBI does appear affordable. Rather, it’s a question of tradeoffs and incentives.

Capitulation, or Alternative?

Whether UBI functions as a capitulation or alternative to neoliberal capitalism depends on whether it stimulates or hinders broader reforms, which mostly comes down to how it’s paid for. For example, the first serious proposal for a guaranteed income in the US economy came from Milton Friedman, a version of which nearly came to fruition during Nixon’s presidency.

Friedman supported a relative of UBI: a negative income tax (NIT). He supported it as a justification for eliminating all other welfare programs. His NIT was a ceiling that prevented any further social programs, rather than a floor creating a more stable foundation for progressive reform.

In practice, a NIT and UBI are quite similar. NIT monitors people’s incomes and only pays out the amount required to have their incomes raised to an agreed upon income threshold (like the poverty line). Whereas UBI would give everyone the cash equivalent of the poverty line, avoid administration costs of monitoring incomes, and adjust taxes to achieve the desired distribution.

What made the difference for Friedman was funding the NIT by folding all existing welfare programs into it. By contrast, a NIT funded only by eliminating a few means tested programs (earned income tax credit, for example), and progressive taxation (perhaps an income tax on both labor and capital), would not dismantle the welfare state, but place it on firmer ground.

This is why funding proposals are crucial to the question of capitulation. They determine whether the balance tips one way or the other. Engaging with the variety of funding options can help us evolve the conversation away from writing off an adequate UBI as impossible.

Instead, we can begin scrutinizing how various funding proposals would alter the economy, and explore what kinds of alterations are both feasible and desirable.

The Human Nature Problem

Then, there’s the question of human nature. If we manage to decommodify significant amounts of time, will we just waste it? Is it worth enacting the largest program in American politics if it enables citizens to just spend more time watching Netflix and going to the beach?

The first response is to recall that the justice of market economies rests upon voluntary exchange. If we agree with Widerquist that a physical basis is required for voluntary trade, the question of how we might live in the aftermath is irrelevant to the imperative of ensuring justice at all scales of market transactions. The specter of UBI recipients watching more Netflix is not sufficient cause to maintain and legitimate an unjust economic world-system. What people do with their time is their prerogative.

But here, there is a profound question at play that ties back into the relationship between economic conditions and human development. Is human nature a fixed essence, or an adaptive process? To what degree can changing socioeconomic conditions actually change the kinds of humans we become?

For seminal economic theorists from Karl Marx, Henry George, on through John Maynard Keynes, decommodifying time has always been associated with the ongoing transformation of human nature. There is no fixed essence of human nature that defines how we’d behave in radically altered conditions. Behavior is adaptive. It is the evolution of material and social conditions that gives rise to new behaviors, and so new humans. This is what Marx means when he writes, “all history is nothing but a continuous transformation of human nature.”

George foresaw this human nature critique, writing:

“But it may be said, to banish want and the fear of want, would be to destroy the stimulus to exertion; men would become simply idlers, and such a happy state of general comfort and content would be the death of progress. This is the old slaveholders’ argument, that men can be driven to labor only with the lash. Nothing is more untrue.”

In worrying about the Netflix-ization of time with an adequate UBI, we’re projecting the kinds of humans we are now into a hypothetical society with radically altered conditions. We’re failing to account for how human nature would itself adapt and evolve alongside new conditions of decommodified time. The projection that we’d waste our time with idling activities like Netflix and the beach neglects that most working class humans today are overworked and barely getting by. Current notions of how we spend our ‘leisure’ time are products of, and responses to, our life conditions.

A recent New York Times headline covering Angus Deaton and Anne Case’s recent book reads: How Working Class Life is Killing Americans, In Charts:

Deaton and Case note the disparity in conditions between those with a college degree and those without as influential in these trends. Further studies build on this. A 2013 Nielsen report noticed a trend where increasing educational attainment correlates with decreasing TV consumption:

In both cases, suicide and TV consumption, educational attainment is strongly correlative with different behavioral outcomes. Higher educational attainment, as Deaton and Case explicitly mention, tends to indicate better material conditions. Different environmental conditions are implicated in different behavioral outcomes.

For George, progress is to democratize the improvement of material conditions by sedimenting them beneath society’s feet as common property. “And out of these bounteous material conditions”, George writes of a not-so-distant future where want and necessity are vanquished, we “would see arising, as necessary sequences, moral conditions realizing the golden age of which mankind has always dreamed.”

George is exuberant, imagining “the man with the muck rake drinking in the glory of the stars”, but the point remains: the decommodification of basic needs (by affording access to them as common property unconditionally available to all) creates the conditions for new kinds of humans. Released from the totalizing grip of needs, desire would remain a propulsive force behind progress:

“Want might be banished, but desire would remain. Man is the unsatisfied animal. He has but begun to explore, and the universe lies before him. Each step that he takes opens new vistas and kindles new desires. He is the constructive animal; he builds, he improves, he invents, and puts together...Man must be doing something, or fancy that he is doing something, for in him throbs the creative impulse; the mere basker in the sunshine is not a natural, but an abnormal man.”

Perhaps so. Even if not, there is a deeper assumption that motivates the human nature critique of UBI. Who are we to judge how others spend their time?

In terms of UBI, what often motivates the time-use critique is the fact that tax dollars are used to fund the program. If some UBI recipients use the money to sustain lifestyles I reject, like smoking weed and watching TV all day, why should I be forced to fund those lifestyles?

This is commonly referred to as the free-rider problem.

The Free Rider Problem

A poverty-level UBI of $12,490 is hardly a living wage for even the most ascetic of citizens; most will continue to work and earn additional income. However, it is plausible to imagine at least some percentage of the population who choose to live off their UBI alone.

These folks will be living off tax-funded income without participating in forms of employment that contribute to that tax base. In other words, they are ‘free riding’ off the earned income of others. Is this fair? Do we owe this kind of financial freedom to each other?

How might this criticism change if we apply it to parents who choose to stay home and raise their children? Does the same sense of unfairness come into play when recipients use UBI to fund socially valuable activities that markets fail to compensate? Surely a devoted parent is worth more to society than an unmotivated office administrator, or insurance salesman?

What about aspiring scientists who use the newfound financial and time freedoms to focus on exploring new theories? Or artists who dedicate their time to creativity? In this sense, UBI functions to extend earnings to those engaged in socially valuable pursuits that markets fail to compensate for.

Where free riding turns problematic is the assumption that willfully unemployed UBI recipients will live in ways that do not create value for society. Receiving “something for nothing”. But this is not only assumed, it stands in direct conflict with empirical studies on how UBI affects labor force participation rates. Even beyond the question of whether UBI would stimulate or stifle economic activity, a larger question looms: are we comfortable letting markets be the judge of what constitutes value?

Using wages as the prime indicator of value-creation solidifies the market's role in determining social value. But much of the progressive left’s movement is about displacing earnings as sole indications of social value. There are forms of value markets systematically fail to recognize, and forms of socially valuable (usually long-term) investments that markets fail to incentivize. Not to mention the forms of negative value that markets stimulate.

In this sense, the free-rider problem might not be a problem at all, but a solution. It functions alongside the market to stimulate forms of social value that markets leave behind.

Another proposed response to the free-rider problem is to shift the narrative frame of UBI. Since progressive taxes that draw from high-earning sectors of society would fund UBI, some claim that UBI is not redistributing the rightful ‘earnings’ of others, but distributes the portion of collective wealth that’s captured by high private earnings. In this sense, UBI is more of a social dividend that formalizes the collective nature of value creation on modern economies.

Consider how this logic of social dividends applies to raising the corporate tax rate, for example. Mariana Mazzucato has demonstrated how much of the iPhone's signature technology is a result of publicly funded R&D. Although taxpayers effectively socialize the risk of this R&D, the financial returns on that investment are privatized, none of which goes back to the taxpayers who (partially) funded the investment. Should not a small portion of the financial earnings from publicly funded innovation return to those who funded the initial research? Isn’t the public entitled to share in the financial returns on innovations our tax dollars paid for?

Similar logic is at play for many high-earning sectors of society. From Google, Apple, to Tesla, Mazzucato shows how stories of value creation systematically neglect the role of public investment. Framing UBI as a social dividend formalizes the collective nature of value creation, paying dividends on the public’s investment in innovations that spur private fortunes.

A common example is the Alaska Permanent Fund, which taxes all mineral (primarily oil) royalties a minimum of 25%. They reason that Alaskan oil belongs to all Alaskans, rather than whoever manages to dig it up first. The tax revenues are deposited into an investment portfolio that each Alaskan shares an equal share in, receiving annual dividends that fluctuate with the stock market. Applying this logic nationally, Matt Breunig’s proposal for a social wealth fund makes every American an equal shareholder in a collectively owned portfolio.

Framing UBI as a social dividend only makes sense if the funding mechanisms draw from areas of society where large private earnings are bolstered by neglecting public contributions. To sufficiently appease free-rider concerns, UBI advocates must demonstrate what sectors of society wind up paying for UBI under their funding proposals.

Futures of UBI Debate